How to Explore the Map Without Going to See the Wizard

I’ve never been pulled into a painting. This says more of me than it does of art. When I’ve attended galleries and attempted to appreciate art, I end up doing something altogether different. I’ll find an interesting work with a bench close by and wait. Sometimes mere minutes pass, other times hours. Eventually a patron, a student of the arts, a socialite, a pipefitter, an accountant, or an unsuspecting passerby will lock eyes with the work, be grabbed by the collar, and hauled inside. Transfixed, pinned to the ether, fragile tension keeping them upright. The body remains, but they are in the painting. With massive works, people seem to stroll straight in, stepping over the frame. With petite pieces, like Michelangelo’s “The Torment of Saint Anthony,” explorers put forth their arms, puzzling over how to crawl through the tiny window. Took decades for me to understand what was happening. Deep into the mystery, the seer reaches at phantoms, whispering and muttering to those on the other side of the frame, and I watch through a glass, darkly. The answer I sought to the question I had not assembled came from a serious woman, into middle age then as I am now. She was not dressed for the theatre, for the saloon, or for the classroom, but attired as though she was off to a picnic. She seemed displeased with the museum, with the patrons, the weather, perhaps even the lighting. She seemed so until I saw her go into the painting.

Her gravity was a singular intent, not displeasure; she was returning to the painting. Sunglasses off, into the clutch. Handkerchief from the clutch. Clutch closed and set gently on the marble at her feet. She squared up her posture, avoiding contact with The Cardsharps. Relaxed her hands, breathed slowly while looking down at her toes, and then she raised her head and leapt into the Caravaggio. I’ve taken some liberties with this account as I felt I intruded on an intimate and powerful experience simply by watching, but I didn’t register at all to her. She remained in poise, never wavering from the painting, as if waiting for her turn to speak, and then she did. I won’t repeat her words as they were meant for her ears, not mine, but she spoke in a clear, deliberate, and quiet voice, dabbing her eyes with the handkerchief, and I knew she was standing on both sides of the frame. Since changing the painting was unlikely, even undesirable, she changed herself to enter the painting, but left part of herself outside to record the experience.

Attempts at Unity

Here are the general avenues for a person to attempt unifying with a person or thing. They are vague for reasons which will become clear later.

Changing others: we might make changes to a person or thing to make it more familiar, a greater likeness of ourselves, so that we may join it.

Physical: changing appearance or physical state of others.

Mental: changing ideas or thinking of others.

Spiritual: changing the composition or will of another’s soul.

To permit these sorts of changes is to permit attempts at unity.

To reject these changes is to reject attempts at unity.

This works from another direction as well, changing ourselves to join others.

Physical: changing our appearance or physical state.

Mental: changing our ideas or thinking.

Spiritual: changing the composition or will of our soul.

We must permit these changes in ourselves when attempting to join others.

We may agree or refuse to change ourselves with respect to attempts at unity.

If attempts at unifying with others are rejected, we are changed but not joined with them.

All of these changes increase the possibility of unity, or make unity less difficult, depending on your perspective. These avenues and directions of change may seem agreeable to you, hardly challenging your prior notions. What of the painting? Making another person into a likeness of ourselves, or making ourselves into the likeness of another person are two routes to connecting with people, without requiring my concept of unity. Human beings are quite similar from the start, and making changes to one another seems a reasonable path. But what of the painting? One clue to understanding this is as follows: the subject-object distinction is not a dichotomy, it is a spectrum. I’ll revisit the strange nature of hammers to carry us towards unity.

Instruments of Change

A hammer is a tool, and lying on the workbench, it is only an object. In disuse, it is not even an instrument, only having the potential to be. When you pick up a hammer, things get weird. By wielding a hammer, you have chosen, consciously or otherwise, to do with that hand only things that can be done with a hammer. It is an extension of you. Your freedom with the hammer-wielding hand is constrained to hammer-related acts, but your agency in that domain is increased. This is a simple, elegant form of unity between a person and an object. We change ourselves to join with the hammer, and the change is so minute and temporary that we hardly notice it.

We can and do change objects to join with them, but objects do not change themselves. This raises a predicament for humanity. Unity is our fundamental, primary urge. On what terms, or even whose terms, do we enact changes to increase the possibility of unity? Not all objects are useful, but when we use them, they are instrumental towards our ends. When is it appropriate to change ourselves or others for instrumental purposes? The answer cannot be, “never,” for if that be the case then we lose all access to tools. We change ourselves when we employ tools, restricting our freedom in exchange for an enhancement of agency. What becomes of a person who is changed to be an instrument? What do we become when we make ourselves into tools in service of other ends? Two instruments which we shape others and ourselves to fit are money and currency. These will receive proper treatment in another piece, but for now I leave these sinister devices on the field.

How people are pulled into paintings should be especially curious. A painting does not seem a useful tool or instrument of any type. For pure utility, photography reigns in visual media, until the forgotten utility of painting is revealed. When people are pulled into a painting, they change themselves to join it. Some are predisposed to being flung into paintings; others, like me, find this metaphor difficult, as the changes necessary aren’t obvious. Metaphor is a powerful function, carrying across domains. Consider the possibility that metaphor is a function we employ, that it enables actual transference. Refusal to believe in this possibility, or worse still, taking the position that transference by metaphor is impossible will endanger your thoughts as fiction.

A person is pulled into a painting, changing themselves to make this possible, but to what end? I did not begin to understand until I witnessed that serious woman be with and of the Caravaggio. She had been in The Cardsharps before, though how many times I couldn’t tell. Whatever changes she made to enter the painting on the first try were enough to bring her back again. Maybe she enjoyed being who she was in the painting. Perhaps she wanted to experiment with different ways of being in the painting. In her case, as I watched and listened, she was learning how she had changed. Her phrasing was interesting, noting how the painting had changed her. The painting did nothing, and I use the phrase, “being pulled into a painting,” to illustrate an accepted fiction. Art can seem to pull us in, as we aren’t typically conscious of the changes we make to ourselves to enter a piece of art. When pulled in, art is a subject we approach, not a mere object, and we ascribe changes to ourselves as effects of the work.

Carried Across

Imagine being in Hobbiton as Gandalf the Grey. Huge wizard confronted with tiny doors and toy chairs, everything out of scale for the old man. Bilbo’s home is well-apportioned and perfectly sized for a hobbit, but Gandalf must change himself physically, at a minimum, to fit into the space. Putting his knees to his chin and crab-walking through Bilbo’s front door. Sitting gingerly on the edge of a hobbit chair. Eating dainty portions with absurdly small cutlery. Being a wizard, Gandalf might well have changed the home to fit him, but he changed himself instead. Physical metaphor. But, Gandalf did not enter Bilbo’s home the way one enters a painting. He did not join Bilbo’s home, he joined with Bilbo in his home. Gandalf had no need to change himself enough to fully join the house, merely enough to enter and be entertained. If he had changed himself fully, he would have become another peculiar fixture of Bilbo’s home.

Consider being a person predisposed to getting pulled into paintings, then being dragged into one you do not want to be in. How about Hieronymus Bosch’s work, The Temptation of Saint Anthony.

The work is a horror, and while facing fear is a means to overcome it, being kidnapped by this piece would be terrifying. How to escape? Rejecting the metaphor, the transference, appears to be the most direct exit, but people who are habitually transfixed by art may need to develop this facility. You could follow the path of St. Anthony, resisting temptation through each panel, changing yourself in that way. You might succumb to temptation and take the easy way out. Or, you could change yourself into something that does not belong in the triptych. Remembering yourself on the other side of the frame is one means, but you might also imagine yourself a cubist eagle and fly out of that nightmare. Having been in the painting and escaped, how likely would you be to return? Have you changed yourself to become more or less compatible with Bosch’s work?

Joining with a hammer can change your perception of the world, even when you are not carrying a hammer. Look at all of the things which want for hammering! This is a persistent mental metaphor, one which can be physical as well. Use a hammer often enough and other objects you pick up might be used as hammers. Yet, a hammer remains a tool, an object where a painting is a sort of subject, as it seems to change us, though it is we who change ourselves to fit the work. It is with all of this in mind, smashing things with hammers and being kidnapped by works of art, that I introduce maps, which lie somewhere between hammers and art.

This is a satellite image of Flathead Lake in Montana. It isn’t a map but does have similarities. You’re looking at Flathead Lake from above, as maps are generally oriented. The image is a simplified view of what is present at ground level; this becomes obvious when trying to magnify a section of the image. The image is also distorted spatially, as the Earth is a spheroid but the image is flat. This looks nothing like Flathead Lake does on the ground, only how it appears to a satellite. There is no sense of scale.

Picture yourself a child on the shores of Flathead Lake. Turquoise waters, clear skies, towering pines, mountains in every direction. Once you’ve taken it all in, some troublemaking adult hands you a copy of the image and says, “This is Flathead Lake.”

“No,” you reply, “this,” waving the image, “is stupid. That,” gesturing to the water, “is Flathead Lake.” The kid ain’t wrong.

There’s no mental gymnastics in understanding photography, and that the satellite image is of Flathead Lake. What this adult didn’t understand was the dilemma presented to the child: choose between dealing with the tangible, sensible, real Flathead Lake, or deal with its abstraction. One of the most challenging concepts and intuitions for a child to learn is that it is possible to be in more than one place at a time. So, annoying grownup and patient kid have a drawn-out Socratic dialogue about how the image of Flathead Lake is not the lake, but it could be. No amount of detail in the image will cause it to become the lake, but a person could join with the image and explore it in a different way than strolling along the shore. Once the kid understands how much simpler exploring the image is than the lake, being both in the image and on the lake becomes not only possible, but also fascinating.

Now the kid wants to explore the lake in a more orderly fashion but finds the image less useful than hoped. Troublesome adult complicates matters by introducing a map of Flathead Lake.

Oooooh, this is not at all confusing to a child who’s never seen a map before. Things have become so abstract that the kid’s only point of reference between the image and the map is the shape of Flathead Lake. And yet, there is more detail in the map than in the image, but the new details are cartoonish. Sensible elements from the image have been abstracted and stripped away, replaced by uniformly sky-blue waters, strange green boundaries, red lines with numbered chevrons, and names, so many names. With another dialogue, the annoying grownup shows the kid where they are both standing on the map in relation to the real and apparent Flathead Lake. But the kid’s reflexes are quick; “We are not standing on the map, we are standing on the lake.” The kid ain’t wrong. The somewhat less troublesome adult nods, then points to a place on the map. The west side of the lake, on Highway 93, where the shoreline juts out into the lake close to a small island, which is close to a larger one. Then the grownup points out to the small island, the one right in front of them. Correspondence between map and territory is established. Now the teacher, once merely a grownup, asks the kid how to get from where they are up to Echo Lake, north of Bigfork. Kid doesn’t need any further instruction, dives into the map and explores possible routes.

A map is a tool for navigation, but unlike a hammer it is not an extension of ourselves when in use; the map permits us to extend ourselves over a broad area, much larger than the space we occupy at any given moment. A map is more than a hammer, but less than a painting, which in joining requires us to change ourselves in ways we may not understand or intuit. Changing ourselves to fit a map is straightforward. We expect navigability of the real terrain correspondent to the navigation we perform in the abstract map. It’s easy to be pulled into a map once you’re used to navigating in it and with it. Let’s try another map, one you may think is no map at all.

Speak the Map Into Being

This is an excellent map, but it’s only useful for one sort of journey. You are accustomed to maps which are drawings; this is a verbal version. What is more troubling is the loss of a frame of reference, as the navigation instructions are all relative. A map of purely relative distances and turns could be drawn from these directions, but it remains a map.

All that to drive 1.2 miles. I chose the route option with the largest number of turns to make things more absurd. This is the sort of map which is difficult to join. If you are driving and your passenger reads these directions aloud, when they are appropriate, you would be joined with your navigator who, in turn, is joined with the directions. Your navigator must extend the verbal map into a space which could be driven through, else merely recite directions and not navigate. If you were to miss a turn and your navigator did not extend the space, then the map would become useless and you might become lost. Speaking of lost…

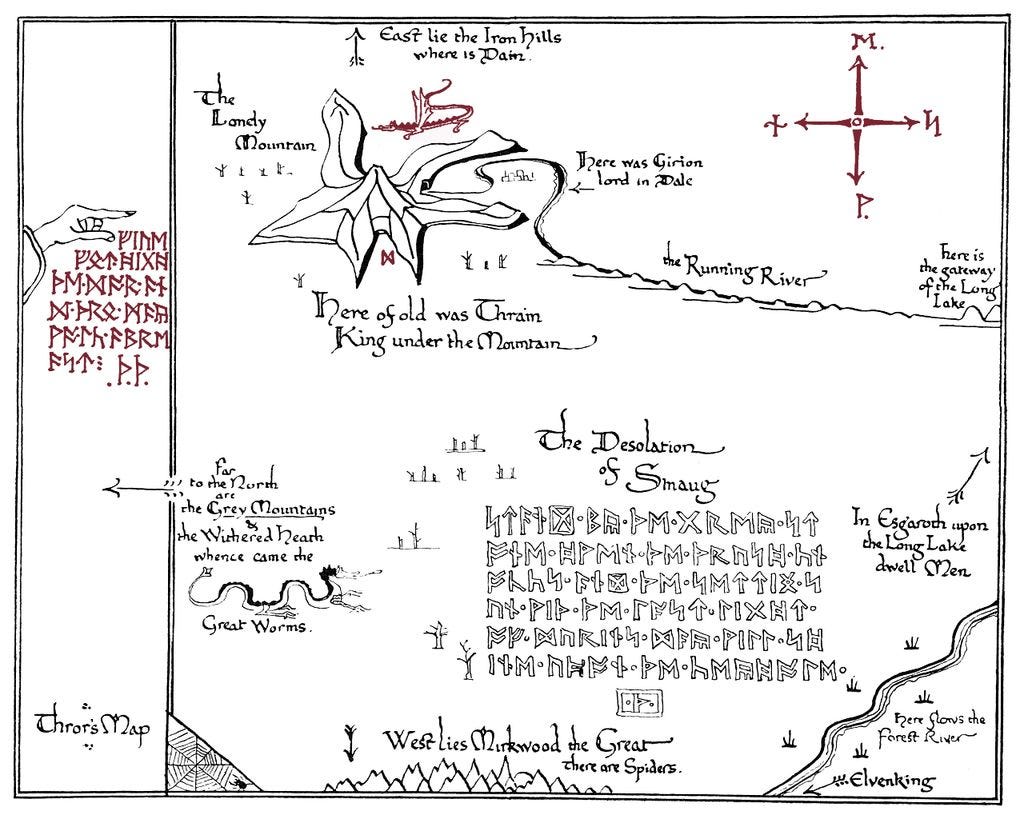

Tolkien loves to get his readers lost in Middle Earth. The very first page of The Hobbit has us lost inside Bilbo’s hobbit-hole before we even learn his name. The story begins in an actual hole in the ground. Tolkien expands the hobbit-hole over the first two graphs, both giving an overall frame of reference and some sense of navigating it, but it’s a lousy map, which is part of the story’s charm. There are wonderful illustrated maps in Tolkien’s works, but being lost in them becomes a joy. I could not hope to count the number of artists and mapmakers who pored over The Hobbit to draw out parts of Middle Earth. Tolkien made maps, not for navigation, but to wander in and have adventures.

Look at this bloody thing! Gandalf brought a map with almost no features on it. Worse still, the runes below The Desolation of Smaug weren’t even visible until Elrond points to them under the light of the moon. The map is crippled for finding the path into The Lonely Mountain without directions given by the moon runes. Magnificent. Thror’s Map is little challenge to join for the reader of The Hobbit, as the reader becomes lost along with the characters. Entering a story involves many changes in the reader, but these changes are often dictated by the author over the course of the story. A painter’s work, by contrast, is given all at once, and the changes required of those viewing the painting are not at all explicit, as they are not with maps. Now is the time to address the skeptics, who have long since left Incredulity, passing through Hesitancy and Suspense just to arrive at Incredulity, leaping over the Chasm of Confusion, sidestepping the Streams of Shock, bounding through the blizzards of Bewilderment, at last arriving at Astonishment. Lovely journey, say the skeptics, but what of aesthetic distance?

I do not know your disposition, my companions, but imagine you are the sort who does not go into maps, into paintings, or into stories. This sort remains separate from what they regard. They never more than touch the surface of anyone or anything. I, for one, am sympathetic to this posture, having been the type to close myself off from connection, relation, involvement. I raise an extreme form of aesthetic distance to carry my point, a metaphor for metaphor, if you will it. Life was something that happened outside of me. Maps were tools. Art was inert and, on occasion, pretty. Stories were pleasant fictions. As for people, they were real, and I was not. You are sampling the ashes of forty years in Hell, one I made as I was the poet of my own damnation, which I escaped once realizing I was the jailer. All this to say, I know aesthetic distance better than anyone, except for a person who once had all of their senses only to have them silenced. We understand people and things in terms of ourselves. When we hold them at difference, we understand neither them nor ourselves. I wish you to have family, friends, and things in the world which are not only familiar and close, but are aspects of you, and for you to be aspects of them in turn. We make the world in our image when we choose to be a part of it. As for me, my life has been amazing since I let myself out of Hell. Making a habit of aesthetic distance is a recipe for misery. Speaking of recipes, here’s one for the skeptics.

Flan de Cajeta

Ingredients:

CAJETA

2 quarts of goat’s milk

2 cups of sugar

1 cinnamon stick

1 teaspoon of baking soda

1 vanilla bean

or 1 tablespoon of vanilla extract

FLAN

2 ½ cups half-and-half

1 strip of lime zest (about 1” wide)

1 vanilla bean

3 whole large eggs

4 egg yolks

¾ cup cajeta (preferably goat’s milk caramel)

Directions:

METHOD FOR CAJETA

Stir together the milk and sugar in a large pot (make sure the liquid only goes half-way up the sides as it’s going to get frothy at one point and you don’t want it boiling over) and add the cinnamon and vanilla (if using a bean, split it lengthwise, scrape the seeds into the liquid and add the pod as well). Bring to a boil on medium heat while constantly stirring. This will take about 15 minutes.

When milk boils, remove from heat and add baking soda (dissolved in a bit of water) to the pot. The mixture will rise and get frothy, but as long as you keep stirring it will be fine.

Place the pot back on the stove on medium heat, and stir and stir and stir (though if you need to take a break, leaving the pot unattended for a minute or so won’t cause any harm to the cajeta). Make sure the milk stays at a gentle simmer rather than a raging boil.

After about an hour, the milk should start to turn golden brown. Remove the cinnamon stick and the vanilla pod. At this point, it will start to thicken fast, so it’s important to keep stirring so the milk doesn’t burn on the bottom of the pan.

Keep stirring until the mixture is a rich brown and thick enough to coat the back of the spoon, which will happen in about 15 minutes.

Pour into a glass container. It should keep in the refrigerator for a week, though mine has never lasted that long.

Notes: You can find goat’s milk at most health-food stores or farmer’s markets. Also, the cajeta gets thicker as it cools, so be sure not to overcook it. If it’s too thick, however, you can thin it by adding hot water.

METHOD FOR FLAN

Preheat oven to 350F

In medium sauce pan, put cajeta, half-n-half, and lime zest. Split vanilla bean lengthwise and scrape seeds into pan. Simmer and stir until smooth.

In a separate mixing bowl, whisk together eggs and yolks. Slowly add to cajeta mixture and stir slowly. Remove from heat and pass through a strainer. Carefully ladle mixture into ramekins.

In a hot water bath, bake for 30-40 minutes until edges are set. Center should still be a bit wobbly.

Remove from water and let cool for at least 30 minutes, flan will continue to set. Un-mold to serve. GOCE !!!

Number Of Servings: 6-8 flan

Preparation Time: 90 minutes

This is a decent recipe, though I’d substitute Turbinado or unrefined brown sugar in the cajeta. Please use vanilla bean, not the extract. I’ve never had lime zest in the custard before, but it sounds interesting enough to try. By the way, this recipe is a map.

Joining the Map

Like the turn-by-turn directions earlier, this has no apparent frame of reference. Instead of navigating by distances and markers, with a recipe you navigate your own knowledge and mastery of cooking. If you were to maintain an aesthetic distance from this map, the recipe, you may not enjoy the results. This recipe is not richly detailed, as the author assumes that whoever is reading already has some cooking knowledge, similar to how the turn-by-turn directions earlier assumed the driver understands traffic laws, conventions of driving, having fuel in the tank, and a host of other things that habitual drivers spend little time considering. A driver changes themselves to drive a car, and while the union between driver and car isn’t as clean and elegant as between hammer and hammerer, drivers can join with cars for driving.

Making flan requires different changes than driving. All of the regulations of driving can be read ahead of being at the wheel, but the responsibilities of driving are learned by doing. The recipe for Flan de Cajeta doesn’t teach the reader how to be a chef in general or a dessert-maker in particular. Think of it as a local map in the far wider map of cooking, only listing turn-by-turn directions from here to flan, presuming you know how to satisfy the initial conditions for making flan, and can perform some techniques to navigate each step. If you were to maintain an aesthetic distance from this map, the recipe, you would be unable to arrive at Flan de Cajeta, because the recipe does not tell you how to be a chef or function in a kitchen. You become a chef by exploring the territory of cooking, piecing together a general map of cooking from many local maps of particular dishes and techniques. Your general map of cooking is not the territory of cooking, but it could be. Stepping into a recipe joins you to a vision of the process to create, step-by-step, and entering this map is made easier by learning different aspects of cooking. Having a larger map of cooking permits a chef to do something in creating a dish that the recipe alone limits: there’s more than one route to arrive at Flan de Cajeta.

I have a special treat for the philosophers, a map they will be unable to dispose of once they’ve seen and understood it.

This is a map generated from Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. The dot in the center is the apperceiving individual. In turn the dot is circumscribed by the boundary of possible experience. And the X, why that’s the transcendental object. Ta-da! Reductive, you say? That question suggests you are beginning to understand maps. My map is not the territory of Kant’s 1st Critique, but I understand the 1st Critique fairly well, so this map could be the territory. This map is absolutely useless for navigating the Critique of Pure Reason if a person doesn’t already know the work. In fact, if I hadn’t named the territory which this map is of, it might have served as a map for an entirely alien domain. The map isn’t the territory, but it could be; to which territory do you refer, sir?

Inhabiting the Map

A painting is not a map. The territory of the painting is apparent, actual. The serious woman who went into The Cardsharps isn’t initially in a map, but she is likely building and expanding one. She contains a map of the Caravaggio, and this is a local map of the painting, probably one of many local maps of particular works, stitched together into a general map of artistry. Her descriptions of items and details in the painting become features and reliefs on her local map. She moves among the boy, the cheat, and the veteran cardsharp drawing paths. They play on as she sits alongside them at the table, whispering to the boy to beware, winking at the cheat, distracting the cardsharp. They play the same hand, again and again, and the scene expands. The serious woman takes the cheat’s knife and menaces the cardsharp, then turns about and robs the gullible boy. On another visit, she draws the curtains beyond the frame, pitching the scene into darkness, and dashes away with everyone’s money. Every hand the same, but she adds to the scene every time. The serious woman stands in three places at once: with the painting in the gallery and observing herself, in the painting as it is, and within her expansive map of the painting. Her representation of the work, her map, is not the painting. In many ways her representation exceeds the painting. She could not change the painting, so she altered her representation of it, remaking it in her likeness, inhabiting it every bit as much as she did her summer dress, for her dress may not have fit her well when she bought it. Her map of The Cardsharps contained not only the reshaped space, but also the changes which she made to herself to inhabit it. Her map of the Caravaggio is not the territory, but it could be.

For a map to be of a territory, it must be possible for the map to be the territory, despite the map never being the territory. Addressing a map as distinct and separate from the territory it represents is nearly a given; a map is not actually the territory. Yet, for the map to have any relation to the territory, it must be possible for the map to be the territory, through the perspective of the person interpreting map and territory. This is a precondition for all representation; without it, you risk doubting your own thoughts and senses. It must be possible for your representation to be reality, else you could not hold the world together, or yourself for that matter. When reality is represented well, metaphor is seamless. Accept metaphor or suffer aesthetic distance. Suffering generally follows a person’s will to suffer, so choose wisely.

Exploring the Map

I assured readers of an earlier piece that I would explain how to explore my map without going to see the wizard.

The map is not the territory. Once you’ve found yourself on the map, you will know this viscerally. Be sure to eat and hydrate before you set out on the map. Not joking. There will be another piece, supplemental to this primer, titled, “How to Explore the Map Without Going to See the Wizard.” There is not an actual wizard, this refers to the Wizard of Oz. Dorothy doesn’t go to see the wizard, she’s been in a coma. Creating an empty metastable space and exploring it will tax your mind and body. Treat this as you would any other strenuous activity, prepare yourself.

I’m satisfied with my explanation, though you may not be. I didn’t give you a list of instructions, turn-by-turn directions, a recipe, a map for exploring my map. You got an adventure instead. So, a better question to me would be, how does one prepare for an adventure, coming to a place? Before Gandalf came to him with Thror’s Map and thirteen dwarves with boundless appetites, Bilbo had no stomach for adventures, yet he hungered for them. Bilbo didn’t go to see the wizard; the wizard came to him, teasing him with a new dish. The first thing you require is will, an aspect of your soul, of your spirit. You must will yourself to come to a place, to adventure, else you starve to join it. For all his protests against, Bilbo craved adventure, but did not know where they would come to, until the dwarves sang of the Misty Mountains.

The second thing you will need is a destination, a place to come to. But Bilbo is of the Shire, what does he know of the Misty Mountains? So, we arrive at the third thing you will need, an origin, the place you begin, for arrival at one place entails departure from another. Gandalf shows Thror’s Map to Bilbo, but the moon runes aren’t yet visible, and Gandalf isn’t aware they exist. The Shire isn’t on the map either, but Gandalf knows how to arrive at the map from where they are at Bilbo’s table. But, Thror’s Map isn’t meant to aid travellers in arriving at The Lonely Mountain, it’s meant to help navigate into the mountain. Elrond later makes the map’s purpose plain by shining new light on it.

Having will, destination, and origin is not enough, unless you intend to fail the journey. You must prepare, improve conditions, change yourself for adventure. Bilbo hosted a smashing dinner for Gandalf and the dwarves, food and drink, song and story. Spirits were raised before their adventure, but they were all changed in other ways. An empty stomach is an anchor, holding you in place, but appetite can urge you towards your next meal. Their destination was not the dinner table but The Lonely Mountain, and hunger is an impediment to travel, so they ate, becoming physically capable of the journey. They changed themselves in other ways, accommodating clothing suitable for the adventure, carrying food, tools, and instruments. Bilbo had not been an adventurer. The Bilbo of Bag End could not arrive at The Lonely Mountain, and so Bilbo had to inhabit Bilbo the Burglar, changing himself to be capable of adventure. The fourth thing you will need is metaphor, for who you are here may not be suitable or adequate for whom you will need to become in arriving there. Physical, mental, and, in word as well as deed, spiritual metaphor.

The final things to bring with you are not necessary, but you may be glad of having them: a map and travelling companions. If Gandalf had dispatched Bilbo to the Lonely Mountain alone with Thror’s Map, would Bilbo have set foot outside Bag End? Adventure did not plainly appeal to Bilbo that he should set out by himself. Many are capable of journeying alone, but if you can travel together, why not? As for the map, it gave Bilbo some sense of the territory, however misleading, but it was through his companions that he was able to navigate.

I have one more question for you. If the serious woman handed you her account of The Cardsharps, her verbal map, do you think you would be able to use it?

Happy trails,

Cameron

Changelog

2022/10/06: Fixed one typographical error.